Saint Maximilian Kolbe and hope. The infused theological virtue of hope compels us onward in trust of Christ’s promises and his unfailing help, strengthening us to live fruitful lives as children of God. We need only look upon Christ crucified to find confident assurance of God’s providential plan of salvific love for humankind.

By Deacon Frederick Bartels

14 August 2012

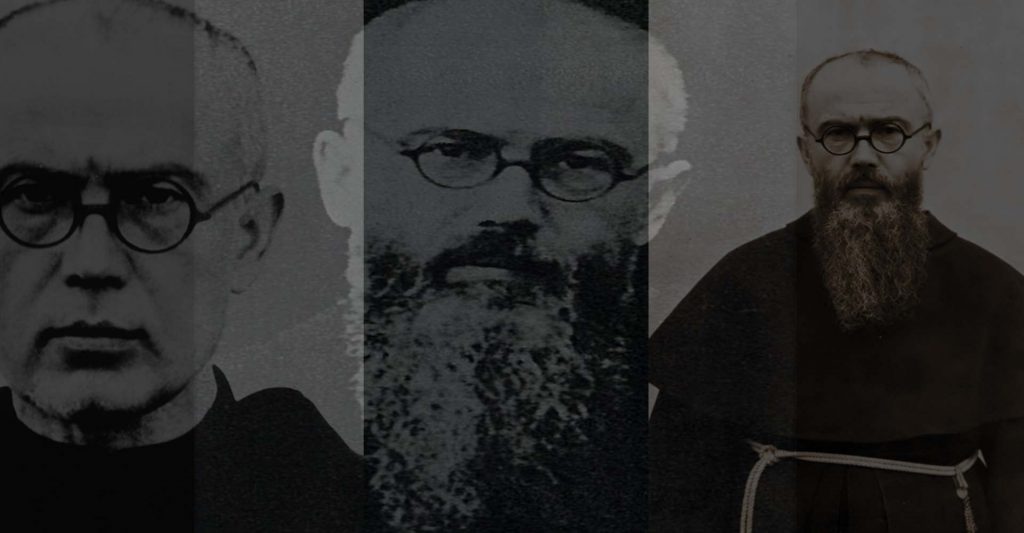

Maximilian Kolbe was born in Poland in 1894, became a Franciscan monk as a teenager, and was later ordained as a priest in 1918 who served a small parish community. But when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, tragic events of human suffering where set into motion in which Kolbe’s destiny would be sealed.

The story is well known. In his labors to protect many Jewish refugees, Kolbe found himself a Nazi target, was arrested, and sent off to Auschwitz in 1941. There, in the midst of the death camp’s unimaginable daily horrors, he worked to encourage his fellow prisoners by setting an example of faith and hope.

One day a prisoner escaped, and, in order to bring an end to any future plans of the same, the guards decided to punish ten inmates of cellblock 14 by condemning them to death by starvation in an underground bunker. One of the ten was Franciszek Gajowniczek, who began to weep and cried out, “My poor wife and children! I will never see them again!” At that moment, Fr. Kolbe calmly and purposefully stepped forward.

“I wish to die for that man. I am old; he has a wife and children.” Such an unusual offer surprised the deputy commandant, who asked Kolbe to identify himself. His response was simple and direct: “I am a Catholic priest.” Those words said far more about the saint than any name possibly could. The commandant agreed to grant the request.

Thrown into the dank, crowded underground bunker with the other men, Maximilian Kolbe continued to set an example of faith and hope, leading his fellow inmates in prayers of praise and adoration of God, singing hymns, and encouraging them to focus on the certain and irrevocable promises of Christ. Looking back on those events, we see that Fr. Kolbe’s food, in imitation of the Savior, was to do the Father’s will (see Jn 4:34): weeks later it became necessary to kill him by lethal injection.

Maximilian Kolbe, a martyr for charity, was canonized by Pope John Paul II on 10 October 1982, with the surviving Franciszek Gajowniczek present. As is normally the case, we begin to glimpse the sublime mystery of God’s loving providence by looking into history, whether it is our own, another’s, or that of humankind collectively, as we cast our eyes and hearts upon the unfolding landscape of salvation in Christ.

The Life of Hope

While there are many things we can learn from the life of St. Maximilian Kolbe, one which stands out above others is the power of hope. Here we do not speak of hope as a natural human virtue, such as we might find in the personal conviction that we will somehow “get through the day” or complete a difficult task, but rather as one of the three theological virtues of faith, hope and charity that are infused into the human person by God. St. Maximilian’s hope did not originate from within himself, but from outside of himself, as a supernatural gift bestowed by the divine Other, from Father to adopted son. It was the virtue of hope that allowed St. Maximilian to continue to trustingly walk forward, even when faced with death itself, confident in the promises of Christ, enabling him to live as a child of God.

The theological virtues of faith, hope and charity “adapt man’s faculties for participation in the divine nature” and “directly relate to God. They dispose Christians to live in a relationship with the Holy Trinity,” and have as “their origin, motive, and object” the Triune God (CCC 1812). The theological virtues, then, are “infused by God into the souls of the faithful to make them capable of acting as his children and of meriting eternal life,” and thus are “the pledge of the presence and action of the Holy Spirit in the faculties of the human being” (CCC 1813).

We could not live and function as God’s children in absence of the infused theological virtues. For instance, devoid of hope, we would lack the ability to trust in Christ’s promises, which would overpower any desire for the kingdom of heaven and eternal life with God as the culmination of human fulfillment. Therefore the joy experienced in looking forward to a life of unending happiness with God would be replaced by the darkness of discouragement — if such a sad state of existence were not supplemented by the distraction of created objects, it would become truly unbearable. However, God gifts us with unceasing encouragement through the virtue of hope, even in the midst of the greatest difficulties, providing us with not only a thirst for what he has planned out of his superabundant goodness, but the certitude that he himself will aid us in journeying ever-more-deeply into his life of love.

Hope is the theological virtue by which we desire the kingdom of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ’s promises and relying not on our own strength, but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit. ‘Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who promised is faithful’ (Heb. 10:23). ‘The Holy Spirit . . . he poured out upon us richly through Jesus Christ our Savior, so that we might be justified by his grace and become heirs in hope of eternal life.’ (Titus 3:6-7; CCC 1817)

The virtue of hope responds to the aspiration to happiness which God has placed in the heart of every man; it takes up the hopes that inspire men’s activities and purifies them so as to order them to the Kingdom of heaven; it keeps man from discouragement; it sustains him during times of abandonment; it opens up his heart in expectation of eternal beatitude. Buoyed up by hope, he is preserved from selfishness and led to the happiness that flows from charity. (CCC 1818)

St. Maximilian Kolbe provides us with a portrait of the theological virtue of hope. In his life, we see not only the external, human manifestations of the virtue of hope, but also learn not to embrace those capitol errors so common in the present age: the unawareness of or disbelief in God’s immanent presence; doubt of God’s all inclusive plan of divine love; the apparent inability to trust in God’s help; and the growing uncertainty over whether God intervenes in human history and in the daily lives of his children.

The Circumstances and Events in Life Cannot Be Mere Coincidence

Further, the example of St. Maximilian’s life teaches us not to fall prey to the temptation of thinking life’s tragedies are somehow entirely random coincidences, outside of Providence, which cannot possibly in any way be linked to our destiny of eternal happiness in God. For the Christian, nothing in life is merely a fluke. Even the very worst of circumstances, such as the horrors found in the death camp of Auschwitz, can ultimately be the very path toward permanent, supernaturally infused bliss and the unending reception of divine love, provided we open our hearts in hope to God and make every effort to live according to his will.

We know that in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose. For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the first-born among many brethren. And those whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called he also justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified. (Rom. 8:28-30)

St. Teresa of Avila wrote:

Hope, O my soul, hope. You know neither the day nor the hour. Watch carefully, for everything passes quickly, even though your impatience makes doubtful what is certain, and turns a very short time into a long one. Dream that the more you struggle, the more you prove the love that you bear your God, and the more you will rejoice one day with your Beloved, in a happiness and rapture that can never end. (qtd. from CCC 1821)

Nearly all of us, at some point or other, realize that we are not in complete control. We may find ourselves, one day, suddenly immersed in some unsolvable tragedy or circumstance for which it seems there can come no good end. Caught up in the situation, all our efforts often become concentrated on attempting to extricate ourselves from whatever seems opposed to our immediate, temporal happiness, while in the process we lose sight of the eternal landscape that lay on the horizon. We can begin to misunderstand our purpose, and overlook the connection between the reality of our life and its events and God’s providence. It is not unlike walking along a path while our gaze remains stubbornly riveted at our feet: our eyes fail to raise upon the rich meadows at our side and the magnificent sunrise that lay beyond. Unnoticed is the sky and the heavens above, infused with an astounding light reflecting the divine Other, whose unceasing whisper beckons us to direct our earthly pilgrimage toward the shores of an unseen yet tranquil, lasting home where the “night shall be no more” (Rev. 22:5).

Christ crucified beckons us to see in hope the “now” and beyond it into eternity. In doing so, aided by the Spirit and thus empowered to live in a new, even astonishing, recreated and transformed way, we join our voices confidently and with conviction to St. Maximilian Kolbe’s: “I wish to die for that man.”

Photo Credit: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12209687

Deacon Frederick Bartels is a member of the Catholic clergy who serves the Church in the diocese of Pueblo. He holds an MA in Theology and Educational Ministry, is a member of the theology faculty at Catholic International University, and is a Catholic educator, public speaker, and evangelist who strives to infuse culture with the saving principles of the gospel. For more, visit YouTube, iTunes and Twitter.

[…] http://joyintruth.com/blog/?p=1438 […]