“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.”

By Deacon Frederick Bartels

7 February 2024

Based on Tradition and Scripture, the Catholic Church has always taught that the Eucharist is Christ himself, his flesh and blood, sacramentally present under the visible signs of bread and wine. The Church Fathers believed this, and many Catholics in the history of the Church were martyred for their faith in the Eucharist. Therefore, a distinct sign of the true Christian faith is the belief that the Eucharist is Christ himself with a corresponding worship of it.

However, Protestants often claim that the Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist is based on a wrong interpretation of scripture. They argue that Jesus was speaking symbolically in John 6, when he said:

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (John 6:53-56).

Notice that Jesus made these statements after the Jews listening to him “disputed among themselves, saying, ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’” (John 6:52). The point is, based on what Jesus said earlier (John 6:51), these Jews believed Jesus was speaking literally. Given the immense importance of his teaching, if Jesus were speaking symbolically, he would have corrected their misunderstanding. However, he did not do so but rather restated his literal teaching more forcefully and explicitly.

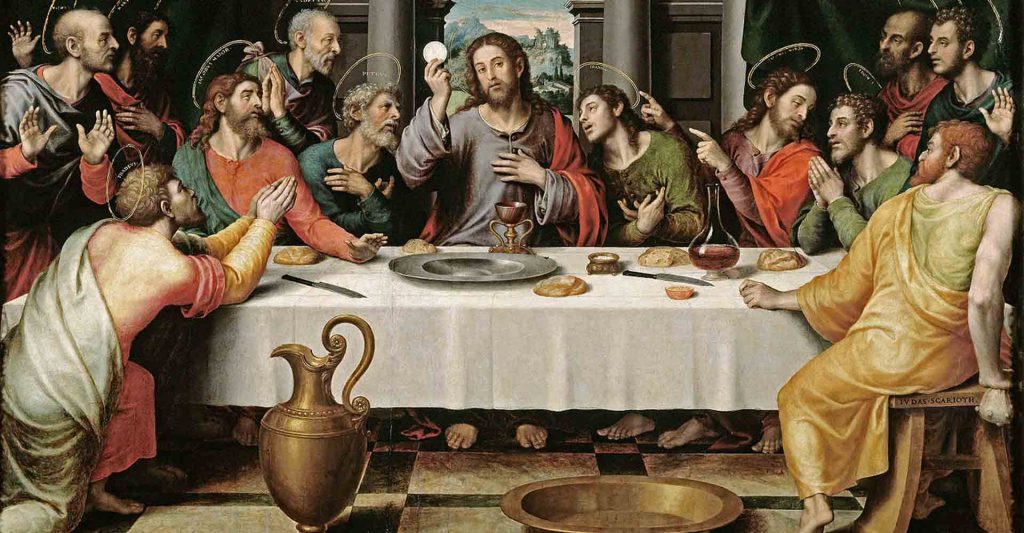

Furthermore, when Jesus took the bread into his hands at the Last Supper, he said, “This is my body” (Mt 26:26; Mk 14:22; Lk 22:19). He did not say, “This symbolizes my body” or “This represents my body.”

Nor did Paul ever teach that the Eucharist is symbolic:

“The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ?” (1 Cor 10:16).

“Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died” (1 Cor 11:27-30).

Catholics Take Jesus at His Word

Catholics take Jesus at his word. Why? Because he is God in the flesh. He has the power to transform the bread into his body and he is incapable of deceiving us on this matter. If we deny his word, we too deny his power and his divinity. If our Lord says of the bread, “This is my body,” that is precisely what he means. And he has the power to make it a reality. When he tells us, “My flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him,” we believe in his divine word.

What did Martin Luther Believe?

But what might come as a surprise is Martin Luther, the man who is generally hailed by Protestants as the catalyst for the Protestant revolution in the 16th century, believed Christ was truly present in the Eucharist, although his theological understanding (consubstantiation) did not align with the Church’s teaching on transubstantiation.

In 1527, Luther published a treatise in which he vehemently argued against his contemporaries, Ulrich Zwingli and Johannes Oecolampadius, who believed that Christ’s words, “This is my body,” must be taken in a figurative, symbolic sense. In response to their wrong interpretation of scripture, Luther wrote:

“Our adversary says that mere bread and wine are present, not the body and blood of the Lord. If they believe and teach wrongly here, then they blaspheme God and are giving the lie to the Holy Spirit, betray Christ, and seduce the world ….”

Luther even goes so far as to call Zwingli, it is assumed, a “pig,” “dog,” “fanatic,” and “unreasonable ass” (Placher, Readings in the History of Christian Theology, 12-14).

In Luther’s Collected Works, Wittenberg Edition, we find this statement: “Who but the devil, hath granted such a license of wresting the words of the holy Scripture?…. Not one of the Fathers … ever said, It is only bread and wine; or, the body and blood of Christ is not there present” (no. 7, p. 391).

Unfortunately, the problems Luther experienced at the outset with arguments, divergent opinions, and contrasting doctrines would only magnify over the centuries, which is self-evident in the tens of thousands of Protestant denominations today. That he was, in large part, responsible for creating an unhealable fissure in Christendom was something he surely recognized, given his statement: “There are nearly as many sects as there are heads” (De Wette, op. cit., III, 61).

Why Does Disagreement Persist?

In any case, for many Protestants from Luther’s day forward, the Eucharist is deemed to be merely a symbol. There is no sound argument from scripture that can be made to support that wrong conclusion, which raises this question: Why does it persist?

There’s lots to say about that.

To begin, there’s the problem of conditioning. When Protestant pastors teach how “Catholics are wrong about the Eucharist” and “it is only a symbol,” offering their personal interpretation of scripture in an effort to back up their views, their flocks often believe they know what they’re talking about and accept it as fact. It becomes something deeply engrained into their psyche. It’s the “food they’re raised on.” In many cases, they never bother to read the Catechism of the Catholic Church to learn what the Church actually teaches, nor do they accept what Catholics have to say—an attitude shored up by anti-Catholic rhetoric, such as “Catholics are Mary-worshipping pagans.”

Then there is the moral issue. It’s no secret that it’s not easy to live virtuously as a Catholic in Christ. The Church’s moral teaching is demanding because it articulates the voice of Christ himself. It’s not only counter-cultural but often counter-protestant. For instance, Protestant pastors and communities often (but not always) teach it is permissible to use contraceptives to avoid pregnancy, divorce and re-marry, and ordain women. The Church teaches the opposite.

There is also “once saved, always saved,” “the sacrament of Confession is unbiblical,” and “there is no such thing as deadly, mortal sin.” Although not all Protestants agree with these teachings, the point is that should a Protestant begin to believe what the Church teaches about the Eucharist is indeed true, there are issues of faith and morals he will likely have to come to grips with, which can be a challenge.

Finally, there is the biblical interpretive issue. The Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura—which is nowhere found in scripture—gets played out in the notion that “every man with a bible is an infallible interpreter of the Word of God.” This practice, however, reduces the Word of God to “every man’s subjective opinion,” which is a recipe for doctrinal confusion and chaos, as history demonstrates. That is the very problem Luther experienced at the outset.

The Church is the Infallible Interpreter of Scripture

Scripture cannot interpret itself. Furthermore, it is clear that man, in and of himself, does not possess the ability to interpret it consistently and infallibly. If we are to have confidence in our understanding of scripture, we must rely on a divinely authorized interpreter. That interpreter is the Spirit-guided magisterium of the Church, the Catholic Church Christ instituted on the foundation of Peter (Mt 16:17-19), bestowed with authority (Mt 18:17; Lk 10:16), as the “pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15).

To be charitable, it is at the least intellectually inconsistent to rip the scriptures from the womb of the Church—the Church whose authority canonized them, and whose authority has defined their meaning for twenty centuries—and use them to attack her consistently held doctrines of the Chrisitan faith, such as that of the Eucharist as the true, substantial, real presence of Christ.

In the end, we must continue to pray for unity and truth—which can only be had in full communion with the Church Christ founded, the holy Catholic Church.

Deacon Frederick Bartels is a member of the Catholic clergy who serves the Church in the diocese of Pueblo. He holds an MA in Theology and Educational Ministry, and is a Catholic educator, public speaker, and evangelist who strives to infuse culture with the saving principles of the gospel. For more, visit YouTube, iTunes and Twitter.

Leave a Reply